Like so many others, I have struggled with existential questions about the purpose of my work and whether I am making a meaningful impact. I often wonder: why do I do what I do every day? Is this corporate job really the best use of my talents and energy? Should I be doing something more meaningful instead, something that truly helps others and makes a difference in the world? What value am I actually bringing to my community and society through my work?

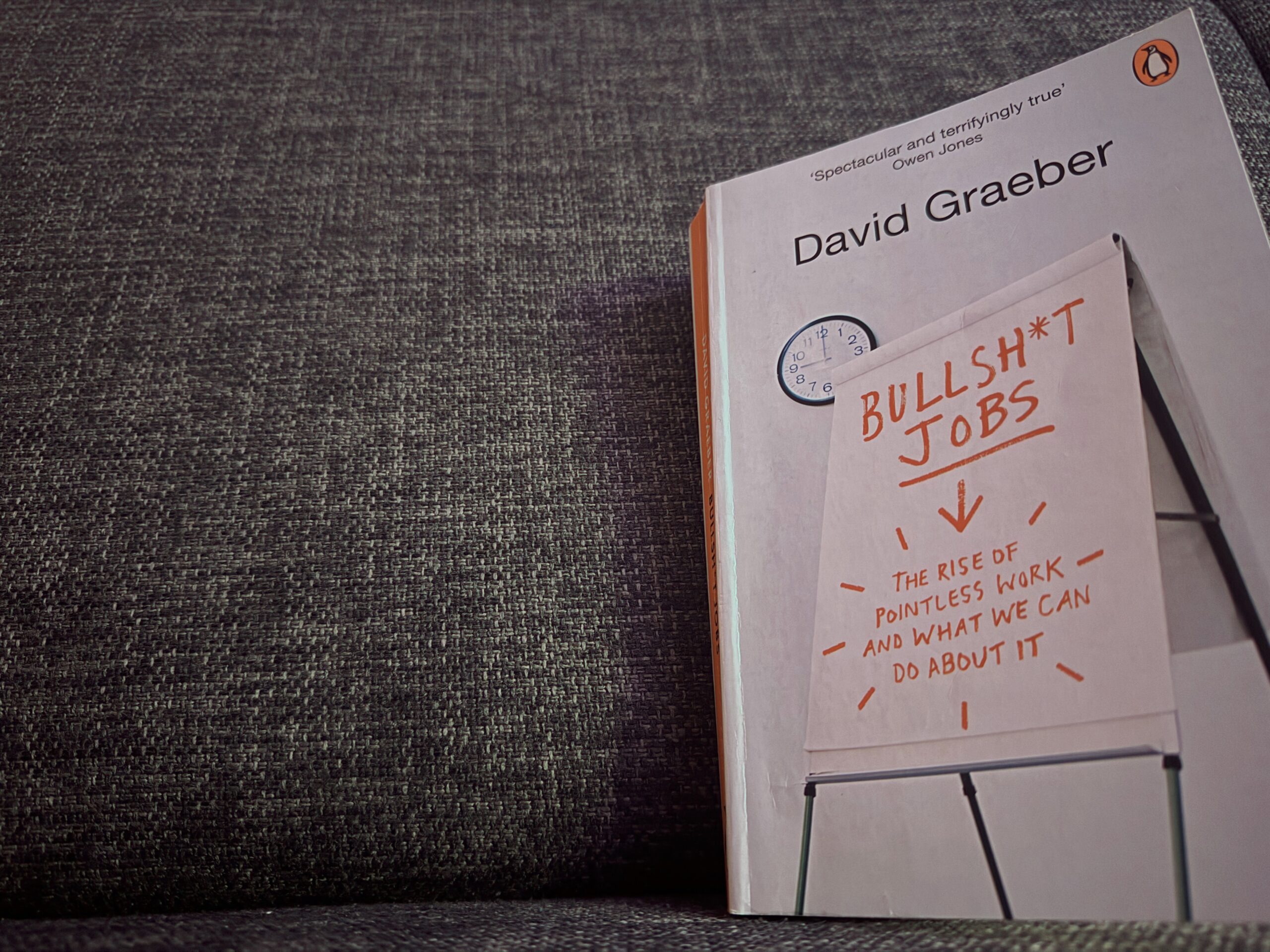

These are the types of concerns that have nagged at me for years, leaving me with a lingering sense that there must be a better path forward, a way to find more purpose and fulfilment through my career. So when I heard about David Graeber’s book “Bullshit Jobs: A Theory”, which argues that many jobs in today’s economy are pointless and actually detrimental to workers’ wellbeing, I was eager to read it. As someone who has often questioned whether I am just “clocking hours” in a job that serves no real purpose, I hoped Graeber’s analysis would provide some clarity and perhaps even inspiration towards finding work that is truly meaningful and valuable.

Now, let us delve into the key areas of analysis presented in the book.

Disclaimer: This review is a creative interpretation and not a direct excerpt from the book.

Unmasking Pointless Jobs

The central thesis of the book is that at least one-third to half of societal work is pointless, unnecessary, or even harmful. This assertion challenges conventional notions of productivity and the alleged value that work holds in our lives.

Graeber identifies 5 types of ‘bullshit jobs’: Flunkies who serve to make others feel important; Goons who act aggressively on behalf of incomprehensible goals; Duct Tapers who remedy problems but do not fix root causes; Box Tickers who create paperwork justifying their jobs; and Taskmasters who assign unnecessary work just to keep subordinates busy.

For me personally, one of the interesting sections of the book was the exploration of Taskmasters. The author describes two distinct types of Taskmasters, shedding light on their roles and behaviors within the context of pointless jobs:

1. Busywork Assigners: According to Graeber, busywork assigners are individuals whose role primarily involves assigning work to others without actively contributing themselves. These individuals often hold positions of authority or supervision but do not engage in meaningful tasks or activities themselves. If they were not present, the work would still be accomplished by subordinates. In essence, they serve as unnecessary superiors, creating a hierarchy that adds little value to the overall productivity of the organization.

2. Bullshit Generators: The second type of Taskmasters identified by Graeber are those who create unnecessary jobs or tasks, such as writing strategic mission statements or generating reports. These tasks serve no real purpose and do not contribute meaningfully to the organization or its goals.

Graeber’s examination of pointless jobs prompts reflection and challenges the functions and missions of various sections and departments within organizations. One quote from “Bullshit Jobs” that particularly resonated with me was a statement by an interviewee of Graeber, who astutely said:

”It's not capitalism per se that produces the bullshit. It's managerialist ideologies put into practice in complex organizations.

David GraeberBullshit Jobs: A Theory

Graeber further explores the psychological toll that such jobs can have on individuals, as well as the broader social consequences of a workforce finding no meaning or fulfillment in their professional lives. He argues that bullshit jobs have led to an “epidemic of clinical depression, social withdrawal, substance abuse, and a pervasive sense of dread and alienation.”

The author also argues that technological advances should have reduced the workweek, yet people work more than ever. He attributes this phenomenon to a prevailing “work ethic” that prioritizes work itself over its actual value and purpose.

Real-Life Examples of Useless Jobs

Has anyone felt like their job is pointless? You’re not alone. Graeber cites studies showing that over half of workers feel their jobs make no meaningful contribution. He includes many real-life examples of individuals in various professions, including those in small jobs and senior positions, questioning the purpose of their work.

In the field of advertisement, Graeber interviewed a person responsible for promoting different products. This individual expressed a feeling that their job was akin to a “bullshit job.” He explained that their primary task was to create a demand for products by persuading people to believe they needed them, rather than focusing on fulfilling genuine needs or creating innovative solutions that improve people’s lives.

Another example in the realm of advertisement revolves around the perception that call center jobs predominantly generate annoyance rather than providing any positive contribution. Some companies employ bait-and-switch tactics, offering free services initially and then demanding subscriptions or fees.

Graeber encountered instances where individuals were hired as assistants solely because their bosses were too lazy to perform specific, menial tasks themselves. These assistants would spend hours each day making numerous copies or manually inputting data into Excel, instead of seeking ways to streamline or digitize the work.

Several examples revolve around the preparation of useless reports for management, which often involve presenting a slew of numbers to create an illusion of success. Similarly, creating and conducting surveys were identified as examples of tasks that lacked genuine purpose or impact.

The main takeaway is that many jobs in today’s economy exist not to produce value, but to generate profit and give the illusion that work is being done. This reveals a fundamental disconnect between what jobs actually accomplish and what workers desire: meaningful work that makes a positive impact.

Another thought-provoking analysis in “Bullshit Jobs” revolves around the discussion of the value attributed to different professions. Graeber points out that while there might not be an officially studied or revealed measure of value, there appears to be an inverse relation between usefulness and pay in many cases.

Graeber highlights the example of medical researchers who often bring significant value to society through their work, such as advancing healthcare treatments or finding cures for diseases. However, their average earnings may not reflect the immense value they generate. On the other hand, workers in the financial sector, who may contribute less tangible or socially beneficial outcomes, often receive disproportionately high compensations.

My Personal Reflections

As I reflect on the topic at hand, I find it essential to offer a more balanced and nuanced perspective regarding the prevalence of useless jobs in today’s world. While “Bullshit Jobs” raises valid concerns, it is crucial to consider the broader context and acknowledge the complexities of our ever-evolving society.

One aspect that particularly stands out to me is the role of technological advancements, globalization, and economic progress. These factors have undoubtedly shaped our modern economic landscape, creating new challenges and opportunities. It’s important to recognize that with these changes, the nature of work has also evolved, necessitating specialized skills and dynamic approaches.

For instance, the finance sector, often criticized in the book, plays a vital role in managing risk, allocating capital, and facilitating economic transactions. While the outputs of finance and economics workers may not always be tangible, their expertise and contributions are crucial for the functioning of today’s complex economies. The increasingly intricate and interconnected global markets demand sophisticated methodologies and approaches that the finance sector provides.

Moreover, the emergence of new trends and industries should not be dismissed outright as purely producing more useless jobs. Instead, we should approach these shifts with an open mind, recognizing that as societal needs change, new jobs naturally arise. It becomes important to evaluate the usefulness and impact of these jobs within their specific contexts, rather than making broad generalizations.

Specific examples are TikTokers, social media specialists, and content creators. While these roles may be met with skepticism by some, we must recognize the evolving nature of media consumption and communication in the digital age. These individuals play a pivotal role in shaping online content, engaging audiences, and driving cultural conversations. While their contributions may not fit into traditional molds of productivity, they cater to the evolving demands and preferences of a technologically connected society.

Conclusion

After reading Graeber’s analysis of so many pointless jobs and the negative impact they have, one can’t help but feel a sense of disappointment, loss and perhaps doubt over their own contribution through their work. While nothing is black and white and some “bullshit jobs” likely provide at least some value, Graeber’s arguments do make you reflect on whether your job truly serves a higher purpose.

I personally have not yet made major changes in my career after reading this book, but the most important thing is to continue enlightening yourself about current trends, developments in the world and, when the right time comes, make the decision to find work that aligns with your true purpose. I hope one day you, the reader, will also find a calling that provides fulfillment and the satisfaction of making a meaningful impact through your work.

While Graeber’s book provides no easy answers, it does serve as a wake-up call to rethink the very purpose of our jobs and reclaim our humanity from the grind of work that serves no real social purpose. Perhaps that rethinking is the first step towards finding work that is truly worthwhile.